Pucker Up: Kisses from the AmberSide Collection

February 9th, 2026 | AmberSide CollectionPeople often come to the AmberSide Collection expecting to see only images of industry. The shipyards, the factories, the visible signs of work that shaped the region. Those images are here, but they sit alongside something quieter and just as present.

Running through the collection is a steady attention to how people are with one another. Not in staged moments, but in passing gestures that happen without ceremony. A hand on a shoulder. A glance across a room. A kiss given without thinking twice.

A kiss can be romantic, but just as often it is familiar, reassuring, playful, or part of a routine goodbye. It happens in kitchens, on pavements, at bus stops, in doorways. It appears where people already share history and care.

Valentine’s Day tends to narrow our thinking about what a kiss means. These photographs open that out again.

Below is a selection of kisses from the AmberSide Collection.

Writing in the Sand: Whitley Bay, September 1987, by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen

Photographed at Whitley Bay in September 1987, this image is part of Writing in the Sand, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s long attention to the coast as a social space rather than just a scenic one.

What gives the photograph its charge is not simply the kiss, but where it happens. The sea front is open, communal, and constantly shared. It is a place for walking dogs, and watching the tide. Within that openness, people carve out small pockets of closeness without stepping away from the flow of everyday life around them.

Konttinen’s series returns again and again to this idea. The coast becomes somewhere that holds many different rhythms at once, where private gestures unfold in full view, and where intimacy sits comfortably inside the ordinary use of public space.

Unclear Family, 1990s, by Richard Grassick

Unclear Family took shape in the early 1990s, when the UK government’s ‘back to basics’ campaign was promoting a narrow image of what family life should be. Grassick’s photographs move in another direction. They pay attention to how care and closeness actually appear in everyday settings, without trying to force them into a single model.

The kiss here is affectionate, instinctive, and unselfconscious. Not staged, not symbolic, just a small act of sibling love that carries more weight than any public slogan about family values.

Across the series, family emerges as flexible and negotiated. It is shaped by who is present, who is absent, and how people look after one another in the spaces they share. The photographs allow these dynamics to unfold on their own terms, offering a view of family life that feels grounded, complex, and recognisable.

Consett, c.1960s, by Tommy Harris

Photographed in Consett in the 1960s, this image comes from Tommy Harris’s years working as both a steelworker and a local newspaper photographer. His pictures were taken for press use, often at everyday events such as sports days, prize-givings, dances and community gatherings. What was once functional reportage is now valued for the small, human details that build a picture of the town’s social life during its industrial peak.

This kiss happens in the middle of a dance, and it forms part of a body of work which shows how community life was held together not only by work and routine, but by the spaces where people came together to celebrate, flirt, dance and enjoy one another’s company.

Steel Works, 1988-1989, by Julian Germain

Steel Works is Julian Germain’s exploration of Consett ten years after the closure of its steelworks, and turns away from the site of industrial loss and looking towards the people growing up in its aftermath.

Writing at the time, Germain asked, “In the past nine years, Consett has changed almost beyond recognition… What identity are people forming for themselves in the new Consett and how do they regard the past?” The project moves through the town looking for answers to that question in the lives of those who live there.

The kiss between these two young people fills the frame. Her arm crosses his chest and shoulder, pulling him close. It feels spontaneous, playful, and youthful.

Within Steel Works, moments like this become part of Germain’s response to changing communities. They show how identity is not carried only through memory or loss, but through the relationships, energy, and the lives of a generation making the town their own.

Survival Programmes: Kid's Den in Garage, Mozart Street, Granby, Liverpool, 1975, by Paul Trevor

From Survival Programmes (1974–79), Paul Trevor worked as part of the Exit Photography Group to record everyday life in Britain’s inner cities during a period marked by unemployment, housing crisis and political fracture. The project refused to reduce working-class communities to statistics or slogans. It stayed with lived experience.

The kisses in this image are awkward, deliberate and slightly self-conscious. They are not romantic spectacle. They are rehearsal. Children trying on intimacy, copying what they have seen, working out the boundaries of closeness and embarrassment in a space that feels half-private, half-communal.

That matters in the context of Survival Programmes. At a time when inner-city Britain was being framed through decline and disorder, Trevor’s photograph insists that adolescence continues. Desire, curiosity and play persist. These young people are not backdrops to policy debates. They are forming identities, relationships and futures in environments already under pressure.

Village is a Global World, 1995, by Jindřich Štreit

In Village is a Global World, Jindřich Štreit turned his attention to former mining communities in South West Durham during a mid-1990s residency, bringing the perspective of a photographer who had long documented rural life in Moravia, Czech Republic, to a region in the UK negotiating its own post-industrial future.

Captured by Štreit in 1995, a woman stands at the gate of her home, holding a baby close and pressing a kiss to the child’s cheek. The gesture is tender. But her eyes move toward the camera. It is not a glance of surprise. It is a look that registers the act of being photographed.

In villages once framed through the labour of the pit, identity had been pictured through work, industry and collective struggle. With that chapter closing, representation does not simply fall away. It has to be renegotiated. In this frame, what is placed before the lens is family, care and a new generation.

The small sign on the gate reading “PLEASE SHUT THE GATE” underscores the sense of threshold. The image stands between private and public, past and present. Štreit’s photograph does not dramatise change. It shows how it is lived and quietly decided, in the everyday act representing what will define a community going forward.

Horden Victory Club, 2000, by Martin Figura

Photographed by Martin Figura in 2000 for Coalfield Stories, this work centres on the Victory Club in Horden, a former colliery town where the pit had closed but the club remained active.

In this image, a couple hold each other in front of the stage. The performer continues under warm lights, but the photograph settles on the embrace. The intimacy is unguarded and untheatrical. What unfolds is neither spectacle nor sentiment, but the kind of closeness that happens in spaces where people feel safe.

Workingmen’s clubs are often described through heritage language, as if they belong to a past. Figura’s photographs resist that. The club appears as a living institution, where identity is carried forward through habit, loyalty and touch. In times of change intimacy does not disappear, it remains visible, woven into music, ritual and community life.

Can I say Shalom?, 1990s, by Miriam Reik

In Can I Say Shalom? Miriam Reik’s returned to the Jewish community she grew up in. In this image, a young man stands between two women in a garden, one leaning in with an exaggerated kiss, the other laughing into his shoulder. It feels playful rather than posed. Arms looped around each other, sunglasses still on, the light catching leaves overhead. The closeness is confident, familiar.

Reik wrote, “This is a story about a community. At the same time, it is also a personal retrospection into a world that both attracts and repels…” That sense of looking again shapes the image. The affection is not sentimental. It is socially fluent, part of a shared language of touch and teasing that belongs to people who know where they stand with one another.

Seen through the eyes of someone who once stepped away and has returned, the attempted kiss here carries more than flirtation. It showcases the dynamics and movements of a social community.

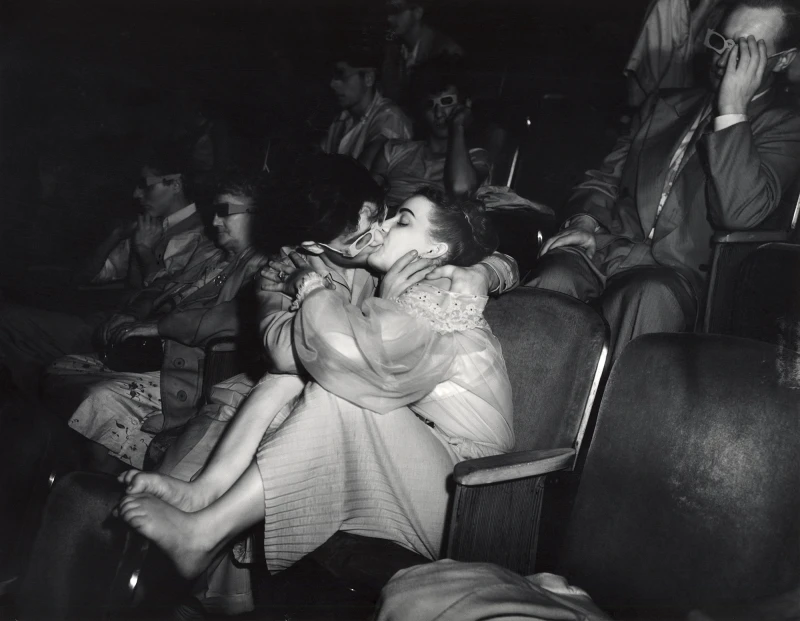

Lover's with 3d Glasses at the Palace Theatre, 1943, by Weegee

Weegee is most often associated with sirens, smoke and the hard glare of the New York night. Yet this photograph holds the same directness and turns it towards something else entirely. A kiss, mid-filmscreening, proving that even in a room built for spectacle, intimacy can take over.

Weegee’s flash isolates the couple from the surrounding darkness, giving their embrace the same weight he at other times gives to bodies in the street and crowds at a fire. Through Weegee's images the city’s extremes are recorded for posterity, but so are its moments of tendernesses.

Across these images, a kiss becomes more than just a sign of romance. They mark how people remain present to one another through change, whether that change is industrial, political, generational or personal. What these photographs hold is not sentiment but connection, the ways affection is carried into public rooms, back yards, beaches and living spaces without announcement. In a collection often associated with labour and loss, these gestures insist on something else: that identity is also formed through touch, humour, care and the everyday decision to stay close.