What is Documentary Portraiture?

February 27th, 2025 | Ellen StoneA portrait is never just an image of a person. It is a negotiation between the person behind the camera and the person in front of it. But documentary portraiture disrupts this balance. It pushes back against the idea of an artist alone defining how a subject should be seen. It questions how portraiture has been used not just to celebrate people but also to define, frame, and at times control them.

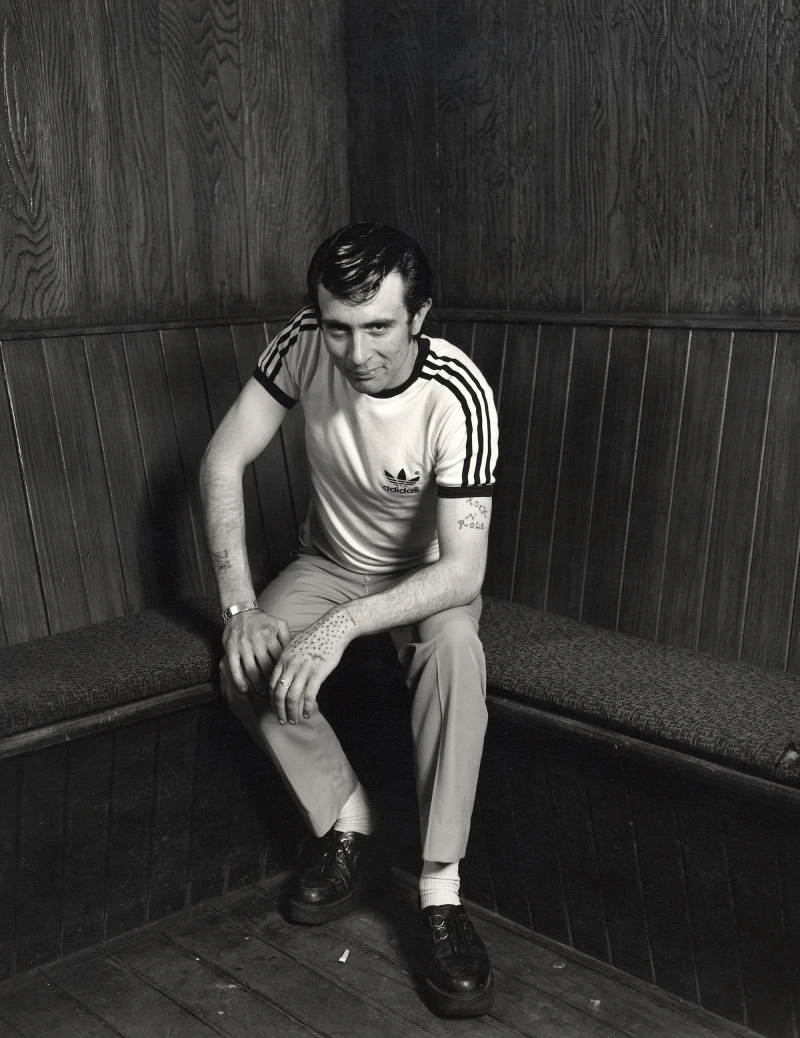

Unlike traditional portraiture, which can flatter and idealise, documentary portraiture is not in the business of airbrushing reality. Its subjects exist within their own environments, shaped by the spaces they move through every day. They are imperfectly human, not staged or polished. A good documentary portrait does not seek perfection because perfection is often dishonest. It looks for presence, the kind that makes you feel as if you have met someone rather than just seen their portrait.

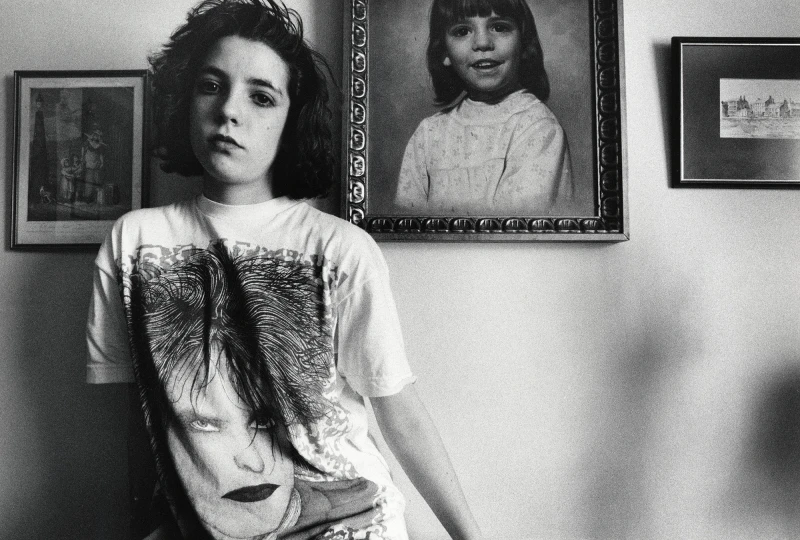

But when does an image become a documentary portrait and not just documentary photography? That happens when the photographer shifts from simply capturing a moment to engaging with a person. It places a person, or small group of people centre stage, where they are not just part of a wider story. Often through closer, more intimate framing, the subject is given a presence. There is an exchange that happens in a documentary portrait, a recognition that what is in front of the camera is not just a subject but a person with their own agency, history and context.

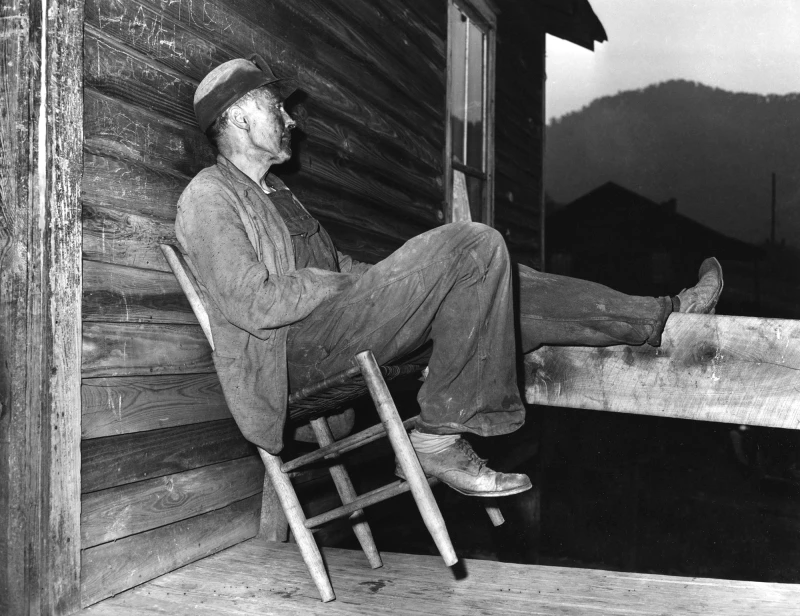

The history of documentary portraiture is deeply tied to the history of documentary photography itself. In the 1930s, photographers working for the Farm Security Administration set out to capture the effects of poverty and displacement across the USA. Alongside images of barren fields and homesteads, they created portraits of farmers and labourers in their exhaustion and resilience. In the 1940s and 1950s, humanist photographers turned their cameras towards everyday life, looking for moments of resilience and dignity. But even in these projects with empathy at the center, questions of agency could be often ignored.

This is what separates documentary portraiture today. Over the past 50+ years, photographers and Collectives, such as the Amber Film & Photography Collective, have redefined what it means to document a person. Their work does not just capture people, it asks them how they want to be represented. It is built on long-term engagement, embedding in communities, and making sure subjects have a voice. This changes everything. The subject is not just an object in the frame, part of someone else’s narrative, instead they are part of the process. Their gaze, their posture, their clothing, their environment, all of it tells a true story. They are not passive, but hold power.

Every documentary portrait is shaped by choice, and every choice has consequences. Framing, composition, focus, light - each one alters how the sitter is perceived. It can change people from isolated to connected, vulnerable to strong. A great documentary photographer uses their artistic vision, but always prioritises the truthfulness of representation. For them these choices are not aesthetic decisions, they are ethical ones.

For much of history, portrait photography has often been used as a tool of control. Early ethnographic portraits turned people into specimens, stripped from their identities. Social documentary and campaign work, although often well-intentioned, has often presented people as symbols of hardship, not as individuals with complex lives and emotions. Even today you can still see images that demand sympathy but at the expense of dignity. Documentary portraiture challenges this. It can ask the viewer to see the subject not as representation, but as themselves.

Documentary portraits feel like real encounters. They aren’t there to give easy answers, nor do they flatter people into ideas. They remind us that looking is never passive. Seeing is an act of engagement, of responsibility, and of recognition. It is not about just showing a face, it wants you to see a person.

Five tips for taking a documentary portrait:

Build a relationship: a great documentary portrait starts before you pick up your camera. Spend some time with the person you’re photographing and listen to their story. Your portrait will come from a place of trust, and someone who is comfortable in front of your lens is going to give a more honest image.

Think about environment and context: a lot of documentary portraiture shows people in natural surroundings. Whether it is a photo taken at work, at home, on the street or in the pub, people’s worlds give texture to your images and can highlight important things about your sitter’s lives.

Look for natural expression: pay attention to subtle facial expressions, body language, and the way the person you’re photographing naturally holds themselves. You don’t want to force a pose or direct too much. Let them settle in and capture them as they are, not as you think they should be.

Don’t overcomplicate the technical aspects: you don’t need complex lighting setups or heavy equipment to take a good documentary portrait. Think about using available light (for example through a window, or under a streetlamp) which will keep the image atmospheric. A smaller camera, or even your phone camera, is also unobtrusive and less threatening, it can help you make the experience of being photographed feel more natural for your subject.

Be ethical: remember every choice you make in taking a photo can affect how your subject is perceived. Make sure you’re always photographing with respect and consent. Remember: photograph others as you would like to be photographed.