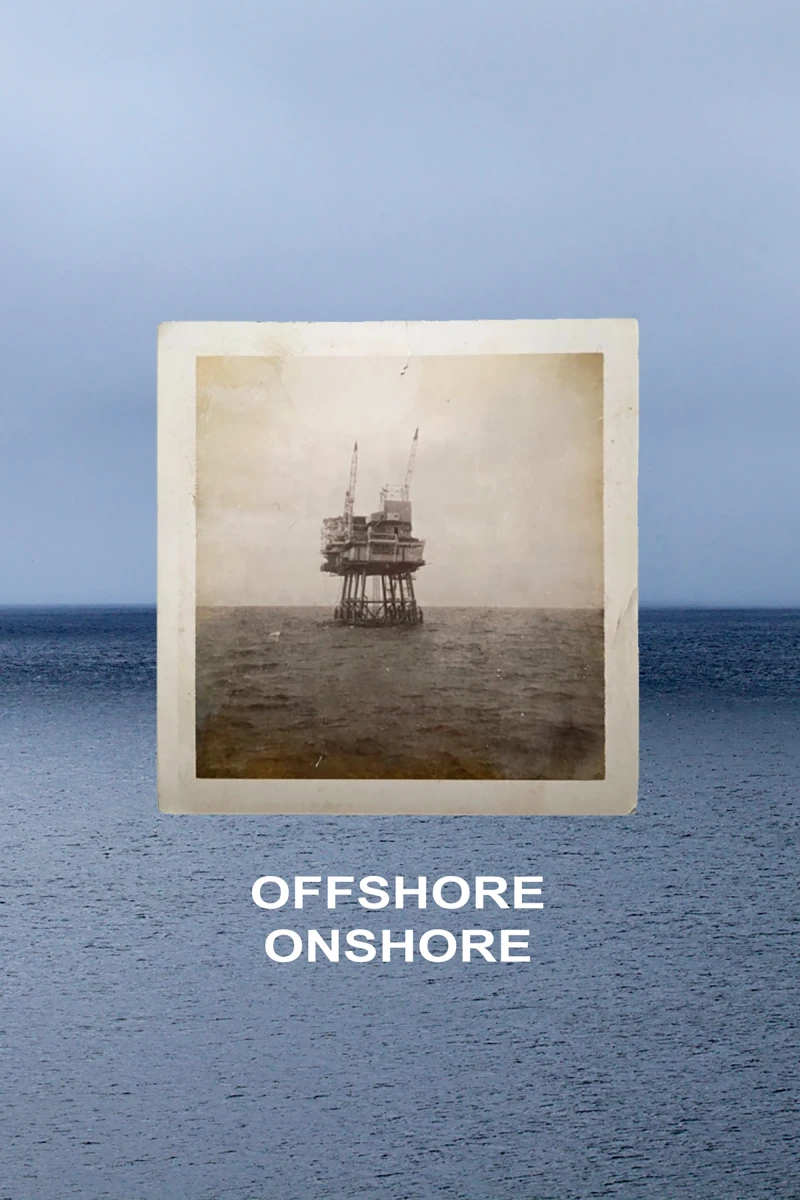

OFFSHORE ONSHORE

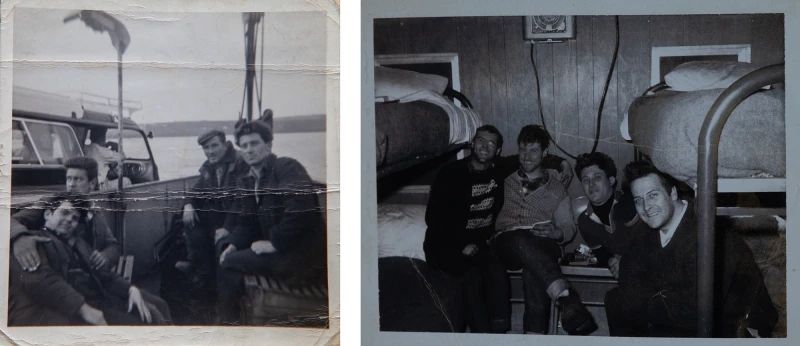

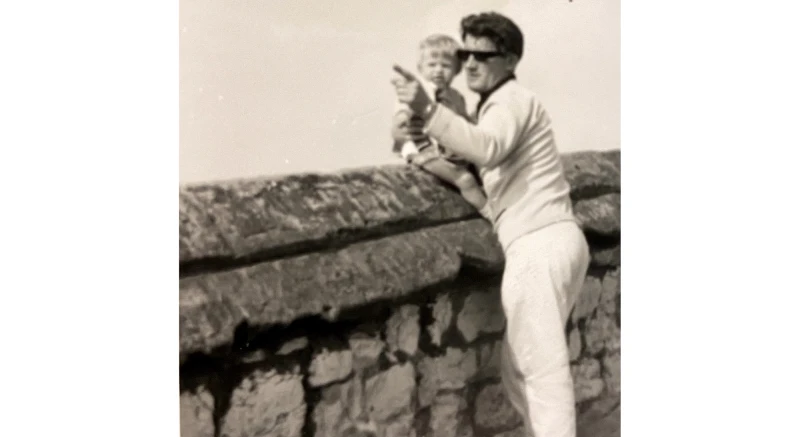

October 31st, 2025 | LK StowA decade after my father died, I discover his album of black and white Polaroids and colour snapshots known as ‘Dad’s boring work photos’. Allan John (AJ) Stow, an electrician and instrument engineer from Hull in north east England, captured scenes from the 1970s and 1980s oil and gas boom in the North Sea, a major turning point in British and European history.

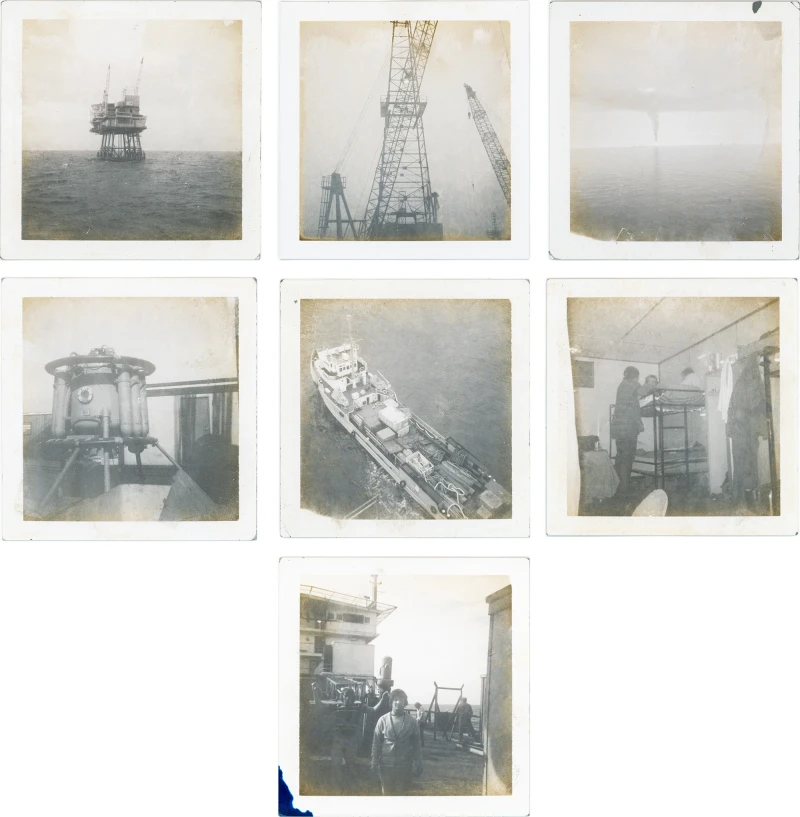

He was one of thousands of men from our region who found new jobs offshore. Using a compact camera, Dad documented some of the first generation drilling rigs and production platforms off the coast of Scotland and the towering steel islands of the Greater Ekofisk, Albuskjell and Valhall oil and gas fields in the Norwegian North Sea. Another photo archive he left behind in his briefcase shows burning oilfields and pipelines scarring the Saudi Arabian desert.

Photos smell of his tobacco, are tea-stained, blotched with ink, or edged with the ghost of his awkward thumb. Here is Dad’s view of the early years of fossil fuel extraction in the rush to drill Earth for ‘black gold’ to feed our insatiable need for heat and fuel.

Some of these early factories in the sea have been decommissioned, dismantled, scrapped or recycled. They are too big to fit in any museum as relics of a once-pioneering industry. Some are being preserved as artificial islands for marine life.

Discovering oil and gas in the North Sea changed the course of global economic history. By the early 1980s Britain had become self-sufficient in oil, and in the 1990s a major exporter of gas. Back then, people thought there was hope in the North Sea.

These were pioneering, adventurous and dangerous years. Finding and extracting oil from deep beneath the hard, boulder clay of the seabed was one of the greatest technical feats of maritime engineering. It was easier to reach the moon than it was to drill for oil beneath the North Sea.

The costs to our planet of exploiting and burning fossil fuels are catastrophic and well-known. Less known are the stories of offshore workers who risked their lives in treacherous waters battered by hurricane storms, 60ft waves and Arctic blasts, to bring hydrocarbons to the surface. Men worked long hours, with little training or health & safety miles from land, and surrounded by hazardous, volatile materials.

Death rates were high due to the big oil operator’s pressure to find oil, extract it and get it flowing fast. Offshore workers were more at risk of death than coal miners and fishermen. Some rig workers suffered psychological disorders and alcoholism. Working offshore for half his life changed my father, onshore, forever.

I was born in 1966, the year commercial oil was discovered in the North Sea in Danish waters - a child of the ‘oil revolution’. Dad’s work offshore was invisible. In our council house we switched on electric lights and the kettle for tea. We turned the car ignition key without a thought as to where our everyday energy was coming from. Our tv news and weather did not warn of the consequences of using these energies. While Dad was out there somewhere in the middle of the sea, we carried on consuming to keep warm, fed and moving.

Discovering oil in the North Sea changed our lives as a region and as a family, for better and worse. Today I live near the East Yorkshire Coast, one of the fastest eroding coastlines in Europe. Each year the North Sea takes another bite out of this land, and heavy rains wash it away.

By LK Stow, 2025